Why use subtlety when a 2x4 will do?

|

This review first appeared in the July 11-12 1998 issue of American Reporter.

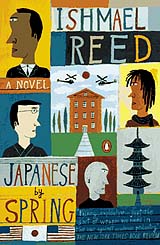

"Japanese By Spring," the recently re-published novel by Ishmael Reed (out in a softcover edition from Penguin), could have been a great satiric novel. And for its first half, it is, poking wonderful fun at the contemporary American fashion of stylizing our politics as much as our wardrobe, of adopting political values not so much for their personal veracity but in order to gain social advantage.

Reed (who was just awarded a MacArthur Foundation fellowship for his work) takes on just about every campus ism in "Japanese": He mocks the middle-class elitism underlying establishment feminism; pans the back-to-Africa paeans of black nationalism; and deftly skewers the back-to-basics movement in higher education, exhuming its silly premise that "European" equates to "universal," that being white is to lack ethnicity.

In the heated debate (especially in California) over race and public policy, Reed has a unique and valuable perspective: He argues that multiculturalism is beneficial, but ethnic fixation harmful. Not too many folks out there are sharp or brave enough to make that distinction, one that hearkens back to the American ideal of the melting pot, of bringing all our different backgrounds together to create something new and stronger. It is an argument at odds with both the racial denialism of the right (which holds that we are all white at heart) and the tribalism of the left (which argues that we are too different to get along and should simply re-segregate).

But Reed is not content to let his wickedly satirical wit do his work for him in "Japanese." No, seemingly worried that even one reader may miss his message that multiculturalism need not be a threat, Reed uses the last part of the novel to whack readers up side the head with a preachiness likely to turn off all but the already converted.

Set at a fictional small liberal arts college in Oakland in the early 1990s, "Japanese" is (mostly) seen from the vantage point of a black professor – Benjamin "Chappie" Puttbutt. Puttbutt is a shameless, self-promoting chameleon who dons whatever happens to be the current intellectual fashion in order to further his career. In the novel (as in real life right now), the crusade du jour is opposing affirmative action – which Puttbutt promulgates with the same smirking righteousness as he earlier advocated radical feminism and black power.

Puttbutt is shocked, then, when despite his obsequiousness he is passed over for tenure in favor of a well-known white feminist. His shock is giving way to anger when the Japanese buy the university and put him in charge of carrying out sweeping changes on campus.

Here is Reed at his best: The scenes in which Puttbutt's former overseers from the various departments come in to beg for their jobs are delicious. Reed further twists the screws of irony as the new Japanese owners begin to sweep out all of the existing curricula in favor of courses in Japanese culture, literature and arts, arguing that any non-Japanese forms are inherently inferior.

But Reed starts to trail off when he brings himself into the book – not as narrator, but as just another character, one Ishmael Reed of Berkeley. Actually, when the references are third person, from Chappie Puttbutt's perspective, it's kind of a neat little exercise. However, when Reed the character assumes the role of narrator, where we have Reed the author creating words for Reed the new narrator to say and think, the whole thing just becomes too self-aware to work, especially as by this time Reed the author has dropped all pretense of satire and is in outrage mode.

It just doesn't work – the book becomes too confusing and the reader has to expend energy on simply following the thread rather than on distilling Reed's thoughts. Plus, the narrative kind of peters out toward the end, leaving no sense of closure. Which in itself is no crime – a book need not maintain traditional linear flow in order to be effective, but when the book begins as a narrative and maintains that form for the majority of the work only to switch gears at the very end ... well, it is understandable if the result is a readership more confused than enlightened.

A further weakness is how quickly the book has become dated. Originally published in 1994 and brought out in softcover last year, it's premise is that Americans of all stripes live in secret fear of the Japanese. Given recent developments in Asia, this now seems kind of silly. Today, of course, Japanese companies are quite busy selling themselves to the highest American bidder as fast as they can – there's no time left for the economic conquest of anyone else.

Also, by taking his argument in favor of multiculturalism to an extreme and arguing that English language and European culture are no more worthy of study than any other, Reed invites easy criticism, such as this: Yoruba may well be a beautiful, graceful language worthy of study, but Shakespeare – for all his faults and alleged racism – was the first major author to write in the then-new language of English. One can make a solid argument that an understanding of Shakespeare (and Twain and Hemingway, for that matter, among other dead white males) is germane to a fuller comprehension of the contemporary English-language writers who have followed. To wit: No matter his fascination with Yoruba, it should be noted that Reed works primarily in English, the language of his audience. Given the complex and subtle use of metaphor and satire in his many works, it isn't hard to see that comprehending a serious writer such as Reed would be greatly facilitated by a greater understanding of English-language literature in general – and satirists in particular, including William Shakespeare.

If you want to know what Ishmael Reed is capable of, check out any of his poetry – better yet, listen to his poetry set to music on two CDS by the jazz project Conjure (on American Clave Records): "Cab Calloway Stands in For the Moon" and "Music for the Texts of Ishmael Reed." Powerful, vibrant works that reach across all strata and divisions and grab you by the throat and prove by example that universality and relevance have nothing to do with ethnicity.